February 7, 2021 by Uwin Lugoda

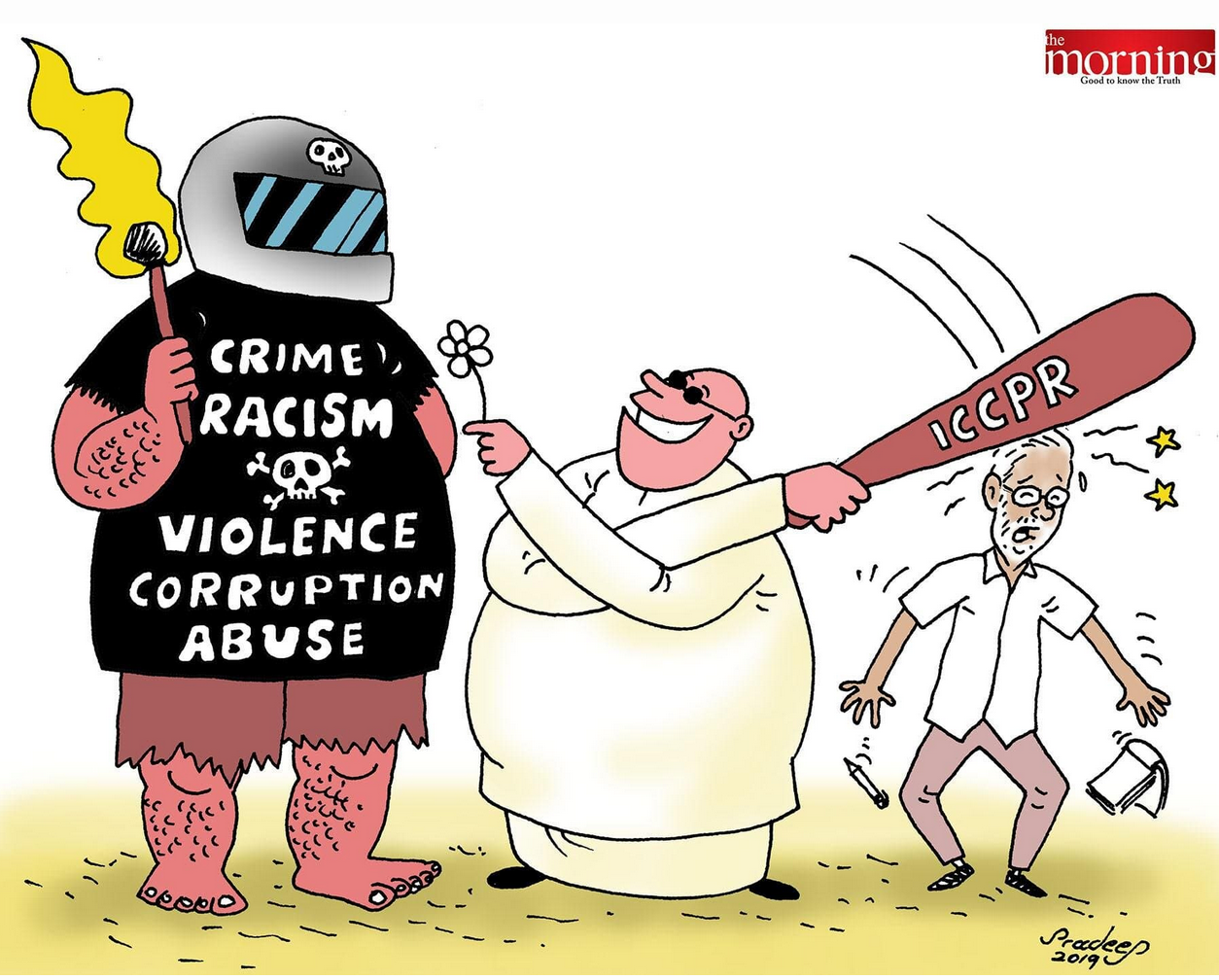

Sri Lankan law enforcement authorities have long faced criticism over the manner in which they use the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The law has acted as the basis for several controversial arrests made over the years, leaving many to question whether local authorities apply ICCPR laws in violation of freedom of speech and expression.

Some of the most notable cases of the inconsistent enforcement of the ICCPR Act are the arrests of award-winning novelist Shakthika Sathkumara for his controversial book and Abdul Raheem Masaheena for wearing a dress depicting a ship’s wheel that was supposedly mistaken for a Buddhist “dharmachakra” two years ago. One of the earliest cases where the ICCPR Act was used was the case of former United National Party (UNP) General Secretary Tissa Attanayake who was indicted in the High Court of Colombo in respect of a statement made by him during the run up to the presidential election of 2015.

More recently, a Tamil journalist, locally known as Gokulan, who was affiliated with Battinews.com, was arrested by the Sri Lankan Terrorism Investigation Division (TID) on 29 November 2020 for posting pictures of Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) Leader Prabhakaran on his personal Facebook page.

What is the ICCPR?

The ICCPR is a law that deals with human rights. The Act was adopted by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly on 16 December 1966 and came into force from 23 March 1976 onwards, in terms of Article 49 of the Covenant. The Covenant respects civil and political rights of individuals, including right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, electoral rights, and rights to due process and a fair trial.

Sri Lanka became a signatory by ratifying the Covenant of 11 June 1980, and in keeping with international obligations, the Parliament of Sri Lanka passed ICCPR Act No. 56 of 2007. The primary purpose of this statute was to recognise rights that are not already recognised under the 1978 Constitution of Sri Lanka.

According to Dr. Gehan Gunatilleke, Attorney-at-Law specialising in constitutional law and international law, one of the main provisions in the Act is Section 3, which incorporates Article 20 of the ICCPR. This provision criminalises the advocacy of war and the advocacy of hatred against a national, racial, or religious group in a manner that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility, or violence.

“This section has to be interpreted very carefully. Three conditions have to be satisfied for it to apply. The statement or expression must: (1) Involve some form of hatred, i.e., enmity of some kind; (2) be directed at a national, racial, or religious group; and (3) amount to incitement, i.e., it must compel others to discriminate or act in a hostile manner, or commit acts of violence,” said Dr. Gunatilleke, speaking to The Sunday Morning.

However, he explained that the Act does not cover defamation of a person, as criminal defamation had been removed from the Penal Code in 2002, therefore giving the Police no jurisdiction to get involved in such a matter, with the only remedy being to seek damages in a civil court.

“It will be an overstep of their authority if the Police investigates defamation. The ICCPR Act should be enforced against those who have incited violence against religious minorities. We have seen scores of such instances. But since its enactment in 2007, the ICCPR Act has not been enforced against any of these perpetrators; it has not resulted in a single conviction in 14 years. So, there is a serious problem in enforcing the Act,” he explained.

Speaking to us on the matter, Minister of Public Security Dr. Sarath Weerasekera explained that local authorities only enforce the ICCPR when it comes to expressions of religion and hatred, which may lead to racial tensions in the community. He went on to state that there are currently 145 individuals in custody under this law, and those convicted cannot be granted bail easily.

“Our law enforcement only gets involved in matters that may lead to racial tension in Sri Lanka. Most of these values of freedom of thought, freedom of religion, freedom of culture, freedom from torture, and freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention have been included in our Constitution. Whatever was left was included when the Parliament of Sri Lanka passed ICCPR Act No. 56 in 2007,” he said.

However, Dr. Gunatilleke stated that the Act has, in the past, been deployed against other actors including writers and human rights activists. These actors have been punished for being critical of religious doctrine and religious actors.

He explained that these actors are not engaging in any kind of incitement. Therefore, he went on to quote UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief Dr. Ahmed Shaheed, who observed that the ICCPR Act has paradoxically become “a repressive tool curtailing freedom of thought or opinion, conscience, and religion or belief” in Sri Lanka.

“In 2015, there was very little knowledge of the ICCPR Act, and in fact, the Government at the time was trying to enact new hate speech legislation. But after civil society and the Human Rights Commission intervened, it was made known that the ICCPR Act already existed, and Sri Lanka didn’t need new legislation. It just needed to enforce the existing law in good faith,” Dr. Gunatilleke said, when asked if local law enforcement authorities have adequate knowledge of the ICCPR Act.

He explained that the law, unfortunately, has not been enforced in good faith in some instances. Instead, it had been used against those who expressed controversial opinions or produced controversial art and literature – none of which falls within the scope of the Act or relate to the three conditions of the Section 3 offence.

In the case of someone being arrested under the Act, Dr. Gunatilleke stated that a habeas corpus application can be filed in the Court of Appeal or a fundamental rights (FR) application can be filed in the Supreme Court in order to seek the release of such a person, if they had been arrested in bad faith.

However, he explained that a magistrate has no jurisdiction to grant bail under the ICCPR Act, and an application has to be made before the High Court for bail to be obtained. He stated that unfortunately, such a process can be time-consuming and is why people like Sathkumara were kept in remand custody for so long before finally being granted bail.

Original post: The Sunday Morning